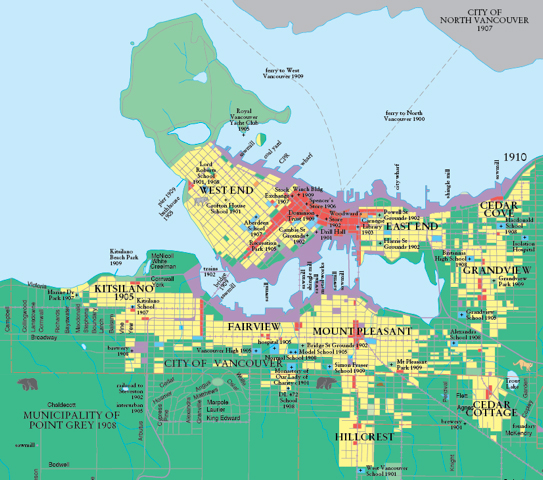

Detail from 1910 map in: Vancouver: A Visual History (1992) by Bruce Macdonald.

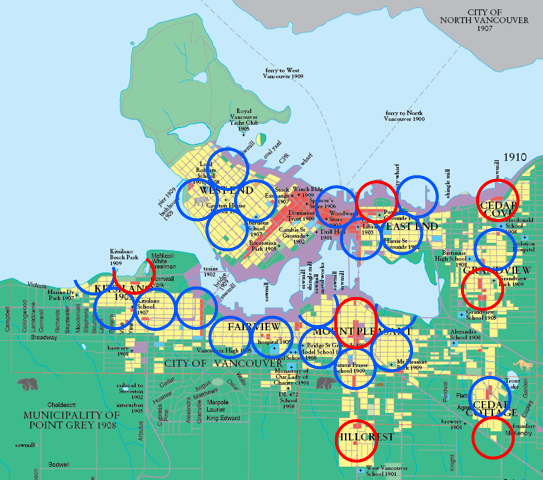

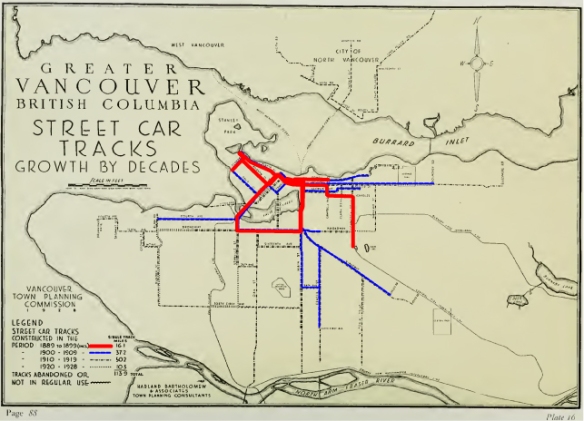

The plan shows the footprint of development in the City of Vancouver 25 years after the railway arrived, and just four years before the opening of the Panama Canal. The latter triggered a building boom in Vancouver in 1908 the full extent of which is represented here. The 1910 Macdonald map presents an enigmatic portrait of a city about to escape the orbit or limits placed by total reliance on walking and horses, and already embracing the possibilities for extension presented by electrified rail transportation. The values of the walkable urbanism are fully on view. Yet, as we compare this map to the growth of streetcar tracks below, it becomes clear that a new set of values is already expressed in the map. Bruce Macdonald comments via e-mail how the walkability of Vancouver’s named urban villages show a keen resemblance to the quartiers.

On the topic of quartiers, I thought you might find the map of interest. It is part of a 1910 map from my book. It shows how during the early streetcar age, before the automobile, Vancouver was developing as a series of named urban villages. Clearly this model is important for achieving the goal of making Vancouver “the greenest city in the world by 2020”. It is also the model that aging baby boomers prefer for their lifestyle, that is everything within walking distance… note that the quartiers on the 1910 map are some of the most popular parts of the city today…

Bruce Macdonald via email, 19 march 2012.

A quartier analysis of Vancouver in 1910

The quartier is the name given to the ‘walkable neighbourhood’. It is the measure on the ground of human scale in urbanism. A quartier can be approximated by taking the distance we walk in 5 minutes (0.25 miles; or 400 meters) and using it as a radius to inscribe a circle. The footprint of that circle or quartier covers 120 acres or 0.5 km2. In urbanism, quartier analysis divides the urban land under study into groups of 120 acre circles to try to learn something about the walkability of the site. A quartier analysis for each of the original ‘urban villages’ follows.

1. The West End. The quartiers here are centred on Davie-Denman-Robson streets that form a horse-shoe shaped urban spine. These streets also carried street car lines (the Davie line completes after 1900). The match between the footprint of the West End and the four quartiers is yet another measure of how fine this part of our city really is.

2. In our work on the Vancouver Historic Quartiers we discovered that if the original quartier (red) was centred at the location of the Hastings Mill Gate, then Gastown, Chinatown, Strathcona and a fourth quartier that we dubbed the “Industrial Quartier” neatly fit around the original. Standing at the Mill Gate, the four original settlement areas are arrayed in terms of easy walking distance. Japantown was the closest, its footprint included in the original mill gate quartier.

3. Relying on Bruce Macdonald’s Mount Pleasant Heritage Context Statement, written for the City of Vancouver, we can locate the principal quartiers for this ‘named urban village’. There is an expectation that Mount Pleasant’s first settlers arrived in the 1860s after the construction of the first bridge over False Creek at today’s Main Street, and the completion of the wagon road to the first provincial capital at New Westminster (Kingsway). The first commercial building is thought to have been erected at the junction of the Kingsway and Fraser, the pioneer road linking to the Fraser River. In 1888 a farmstead was located on the shores of East False Creek near China Creek Park. The park was named after neighbouring Chinese-owned farms. In 1915, just five years after this map, the arrival of the Great Northern Railway (CN), the construction of the Granview Cut, and filling the east side of False Creek completely altered the area. In 1888 False Creek School (later Mount Pleasant) opened at the Kingsgate Mall site, the brick building on 6th & Main was constructed, and many houses cropped up nearby. The intersection of 7th, Kingsway and Main served as the village centre with the Western Front one block east. In 1910, 9th Avenue was renamed Broadway, and Westminster Avenue became Main Street. The Lee building (1912) and the Old Post Office (Heritage Hall, 1916) bookend the territory developed with the migration north along the streetcar line.

1929 Bartholomew Plan

4. Fairview bears the hallmarks of a streetcar suburb following Broadway as an urban spine with service in place by 1899. Streetcar service on the Broadway urban spine extending as far as Granville Street, then turning north and heading for downtown over the Granville Street Bridge will be a shaping influence on the development history of Broadway between the Bowmac Sign (Toys-R-Us) and the Lee Building .

5. Grandview is likewise connected to the early streetcar line on Commercial Drive linking to the Interurban service to New Westminster. The first phase of implementation turns west at Commercial & Venables, then north at Campbell, and west on Powell Street (Japantown). Traces of this route alignment can still be found at Commercial and Venables.

6. Cedar Cove appears to be a settlement on the shoreline alongside the CPR main trunk.

7. Cedar Cottage may have had its origin on the Kingsway Wagon Road predating the arrival of the streetcar. However, on the 1910 Macdonald map, development is ten minutes walking distance from Kingsway. There is a great pair of old row houses on the east side of Clarke at 19th—horribly renovated, yet perfectly stabilized in stucco awaiting a renaissance in the future. These likely belong to this era.

8. Hillcrest lies on the Main Street streetcar line extension completed after 1900. Its location vis-a-vis the quarry at Little Mountain needs to be explored further. The link between the Main and Fraser streetcar lines is shown occurring on 34th Avenue. This is problematic today, since it is 33rd Avenue that moves through the cemetery.

9. Kitsilano. My inclination, without research to shed light into the matter, is to centre the original quartier on Yew & Cornwall. If this is correct, then the development history for this area runs along 4th Avenue, on the purpose built double streetcar line that by 1910 had opened a new suburb to the city.

However incomplete and tentative, the quartier analysis bears out Bruce Macdonald’s observation. The convenience of living within easy walking distance of ‘named urban village’ cores remained a key determining feature of Vancouver quartiers, even as these multiplied, increasing in geographic distance from the centre along the new street car lines. Living within easy walking distance of a ‘named urban village’ cores, and streetcar service, appear to be the two key determinants for development in Vancouver circa 1910.

Pingback: The Iron Lady’s dementia and the signal to cities | City Caucus

Bruce MacDonald provided great insight by sending the plan of early Vancouver. Note how what has caught your attention in the comment sets up the neighbourhoods to receive transit. In the final analysis, getting to ‘good’ urbanism requires building a set of moving parts optimized for human use, and then having the various parts working together, and re-inforcing each other. The town centre model of the regional plan is really too one-dimensional. Each regional centre needs to be ringed by six walkable neighbourhoods or quartiers.